- Original Link

- Updated on November 17, 2021

- Authors:

- Anthony Mathur (Centre for Cardiovascular Medicine and Devices, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK)

- Alice Reid (Centre for Cardiovascular Medicine and Devices, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK)

全文摘要

这篇文章是一篇关于细胞疗法在心脏病治疗中的临床应用和前景的学术论文,主要介绍了细胞疗法在急性心肌梗塞、慢性缺血性心力衰竭、扩张型心肌病和难治性心绞痛等不同心脏疾病中的应用和挑战。

以下是对这些核心内容的简要概述:

- 细胞疗法的背景与挑战:

- 心力衰竭患者数量不断增加,传统药物治疗效果有限。

- 心脏再生能力有限,动物实验显示细胞疗法有潜力改善心脏功能。

- 临床试验面临细胞类型选择、移植方法、安全性和有效性等挑战。

- 理想细胞类型的选择:

- 理想细胞类型应具备修复心肌能力、易获取、安全性高、无免疫原性、易储存和运输、成本效益高等特点。

- 干细胞具有最大的修复潜力,但目前没有细胞类型完全满足所有标准。

- 不同细胞类型的应用与局限:

- 胚胎干细胞(ESCs):具有广泛的分化潜力,但存在伦理、免疫排斥和肿瘤形成等问题。

- 诱导多能干细胞 (iPSCs):具有与胚胎干细胞相似的潜力,但存在肿瘤生成风险和细胞生产效率问题。

- 自体成体干细胞:如骨髓间充质干细胞 (MSCs) 和脂肪来源干细胞 (ADSCs),相对安全但分化潜力有限。

- 急性心肌梗塞中的细胞疗法:

- 临床试验显示细胞疗法在急性心肌梗塞中具有一定的安全性和可行性,但效果不一。

- 骨髓单核细胞 (BMMNCs) 是最常用的细胞类型,输注方式多为冠状动脉内注射。

- BAMI 试验等大型临床试验面临患者招募和成本问题。

- 慢性缺血性心力衰竭中的细胞疗法:

- 细胞疗法在慢性心力衰竭中显示出改善症状和心脏功能的潜力。

- 骨髓来源细胞、间充质干细胞和心脏干细胞等多种细胞类型被用于临床试验。

- 临床试验表明细胞疗法安全,但需要更大规模的研究来确认其长期效果。

- 扩张型心肌病中的细胞疗法:

- 细胞疗法在扩张型心肌病中显示出改善心脏功能和症状的潜力。

- 临床试验中使用的细胞类型包括骨髓单核细胞、间充质干细胞和 CD34 + 细胞等。

- 结合细胞因子治疗显示出更好的效果,但具体机制仍需进一步研究。

- 难治性心绞痛中的细胞疗法:

- 细胞疗法在难治性心绞痛中显示出改善症状和心肌灌注的潜力。

- 临床试验中使用的细胞类型包括骨髓单核细胞、CD34 + 细胞和脂肪来源干细胞等。

- 大规模临床试验如 RENEW 因招募问题终止,但现有数据表明细胞疗法安全有效。

这篇文章为细胞疗法在心脏病治疗中的应用提供了全面的概述,通过分析不同细胞类型和治疗方法的优缺点,探讨了细胞疗法在心脏病治疗中的前景和挑战。

相关研究

| 研究名称 | 年份 | 细胞类型 | 目标患者 | 干预途径 | 样本情况 | 终点设计 | 主要结果 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESCORT; NCT02057900 [1] | 2018 | hESC 衍生 CD15+ Isl-1 + 祖细胞 | 严重缺血性左室功能障碍 LVEF≤ 35%;MI 6 月以上 | 嵌入纤维蛋白补片,CABG 时经心外膜递送 | 6 | 1 年安全性 | 短期和中期技术可行且安全,无肿瘤或心律失常,症状改善 |

# Introduction

Interventional cardiology is a key player in the field of regenerative medicine; cell delivery to the heart is more advanced than to any other organ, which is partly due to interventional cardiology’s success in taking on the challenges of translational medicine.

介入心脏病学在再生医学领域扮演着关键角色;心脏细胞输送技术比其他任何器官都要先进,这在一定程度上归功于介入心脏病学成功应对了转化医学的挑战。

So, what has driven this partnership? Although primary angioplasty has transformed the outcome of acute myocardial infarction, the number of patients suffering with heart failure has doubled globally over the past 30 years.

那么,是什么推动了这一合作关系?尽管直接血管成形术已显着改善了急性心肌梗死患者的预后,但过去 30 年间,全球心力衰竭患者数量却翻了一番。

In Europe, 15 million people are living with heart failure [2] , [3], leading to 2 million admissions a year [4] and an expenditure of €15 billion (across 11 countries) [5].

在欧洲,有 1500 万人患有心力衰竭,这导致每年 200 万人次的住院,并带来 150 亿欧元(横跨 11 个国家)的费用支出。

The processes of myocardial damage and adaptation that lead to heart failure were once thought to be irreversible as the heart was considered a terminally differentiated post-mitotic organ.

心肌损伤与适应过程导致心力衰竭,这一过程曾被认为不可逆,因为心脏曾被视为终末分化、不再分裂的器官。

However, this dogma has been challenged, particularly with the demonstration of continued cell division within the adult heart following injury [6].

然而,这一教条已受到质疑,特别是成年心脏在损伤后仍能持续进行细胞分裂的现象得到证实。

Researchers have also isolated and identified resident cardiac stem cells which can differentiate into multiple cardiac cell lineages such as cardiomyocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells [7].

研究者们还分离并鉴定了定居于心脏的干细胞,这些细胞能分化成多种心脏细胞谱系,如心肌细胞和血管平滑肌细胞。

However, the human heart’s own self-renewal capabilities cannot overcome the massive loss of cardiomyocytes (up to one billion cells) seen in acute myocardial infarction and heart failure (unlike non-mammalian vertebrates, such as the zebrafish, which have demonstrated the ability to regenerate up to 20% of the left ventricle following injury [8]).

然而,人类心脏自身的自我更新能力无法弥补急性心肌梗死和心力衰竭时的心肌细胞大量损失(多达十亿个细胞),这与非哺乳类脊椎动物(如斑马鱼)不同,后者已被证明有能力在受伤后再生多达 20% 的左心室。

There is, therefore, a drive to determine whether the human heart can also be directed into eliciting a regenerative response following injury; either through the up-regulation of its own intrinsic repair mechanisms or through the addition of biological therapies such as cell-based treatments.

因此,人们致力于探究人类心脏在损伤后是否也能激发再生反应;无论是通过上调其自身内在修复机制,还是借助生物疗法,如基于细胞的治疗方法。

Trials have been performed in four distinct clinical settings: acute myocardial infarction, chronic ischaemic heart failure, dilated cardiomyopathy with a non-ischaemic aetiology and refractory angina.

已在四种不同的临床环境中进行了试验:急性心肌梗死、慢性缺血性心力衰竭、非缺血性病因的扩张型心肌病及难治性心绞痛。

Although the therapeutic benefits seen in animal models have yet to be fully translated into man, these early Phase I/II trials provided important safety data and allowed interventional techniques to be refined.

尽管动物模型中观察到的治疗效益尚未完全转化为人类临床应用,但这些早期 I/II 期试验提供了重要的安全性数据,并促进了介入技术的优化。

Cell therapy remains an exciting, novel treatment strategy and this chapter will provide an overview of the cellular mechanisms of cardiac regeneration and repair, a review of the latest clinical trial data and a summary of the field’s current challenges.

细胞疗法仍是激动人心的新型治疗策略,本章将概述心脏再生与修复的细胞机制、最新临床试验数据回顾,并总结该领域当前的挑战。

# FOCUS BOX 1

Rationale for cell-based therapy 细胞疗法的基本原理

- The incidence of heart failure (either as a consequence of acute myocardial infarction or heart disease) continues to grow worldwide.

心力衰竭(无论是急性心肌梗死还是心脏病的后果)的发病率在全球范围内持续上升。 - Despite modern pharmacological therapies targeting heart failure, related morbidity and associated health economic costs are increasing.

尽管有针对心力衰竭的现代药物疗法,但相关的发病率和相关的医疗经济成本却在不断增加。 - Cell-based therapies provide a method for delivering regenerative medicine that can potentially decrease the health and economic burden of heart failure.

细胞疗法提供了一种再生医学的方法,有望减轻心力衰竭带来的健康和经济负担。

# What is the ideal cell type for cardiac repair ?

The ideal cell type for cardiac repair should possess the following characteristics:

心脏修复的理想细胞类型应具有以下特点:

- Ability to repair/regenerate damaged myocardium

修复 / 再生受损心肌的能力 - Easy to obtain

易于获得 - Safe (no tumour formation/toxicity)

安全(无肿瘤形成 / 毒性) - No immunogenicity issues

无免疫原性问题 - Easy to store

易于储存 - Easy to deliver

易于运送 - No ongoing ethical issues

没有持续的伦理问题 - Cost-effective

具有成本效益

Stem cells offer the most potential to fulfil the first prerequisite characteristic, namely the ability to contribute to cardiac repair. Although several different kinds of cell type have been shown to fulfil this criterion there is currently no cell type that meets all of the criteria above.

干细胞提供了实现第一个先决条件的最大潜力,即有助于心脏修复的能力。虽然有几种不同的细胞类型已被证明符合这一标准,但目前还没有一种细胞类型符合上述所有标准。

# Stem cell potential – an overview 干细胞潜能 - 概述

Stem cells are defined by two unique characteristics: they are unspecialised cells capable of unlimited self-renewal and they can differentiate into more specialised cells that form organs.

干细胞的定义基于两大独特特性:它们是未分化的细胞,具有无限自我更新的能力;同时,它们能分化为构成器官的更特化细胞。

The ultimate stem cell is the zygote which can develop into all cell types including the embryonic membranes - this potential is termed totipotent.

终极的干细胞是受精卵,其能发育成包括胚胎膜在内的所有细胞类型,这种潜能被称为全能性。

The developing embryo contains embryonic stem cells ESCs which are pluripotent as they can develop into cells from all three germinal layers (the mesoderm, endoderm and ectoderm) and produce all the tissue types needed to form a functional organism.

发育中的胚胎含有胚胎干细胞 ESCs ,这些细胞具有多能性,因为它们可以发育成来自三个胚层(中胚层、内胚层和外胚层)的细胞,并产生形成功能性生物体所需的所有组织类型。

Developed adult organs also contain undifferentiated stem cells - adult (somatic) stem cells ASCs – but, these occur in far fewer numbers.

发育成熟的器官同样含有未分化的成体(体细胞)干细胞 ASCs ,但其数量远少于其他阶段的干细胞。

These cells were once thought to be limited in differentiation potential and only able to repair and replenish tissue in the organ in which they resided.

过去认为,这些细胞的分化潜能有限,仅能修复和补充其所在器官的组织。

However, ASCs have been shown to “transdifferentiate” into cell types from different germ layers (a property referred to as plasticity), which has been demonstrated in several scientific studies [9] , [10].

然而,研究表明,ASCs 具有 “跨分化” 能力,能够转化为不同胚层来源的细胞类型(这一特性被称为可塑性),这在多项科学研究中已得到证实。

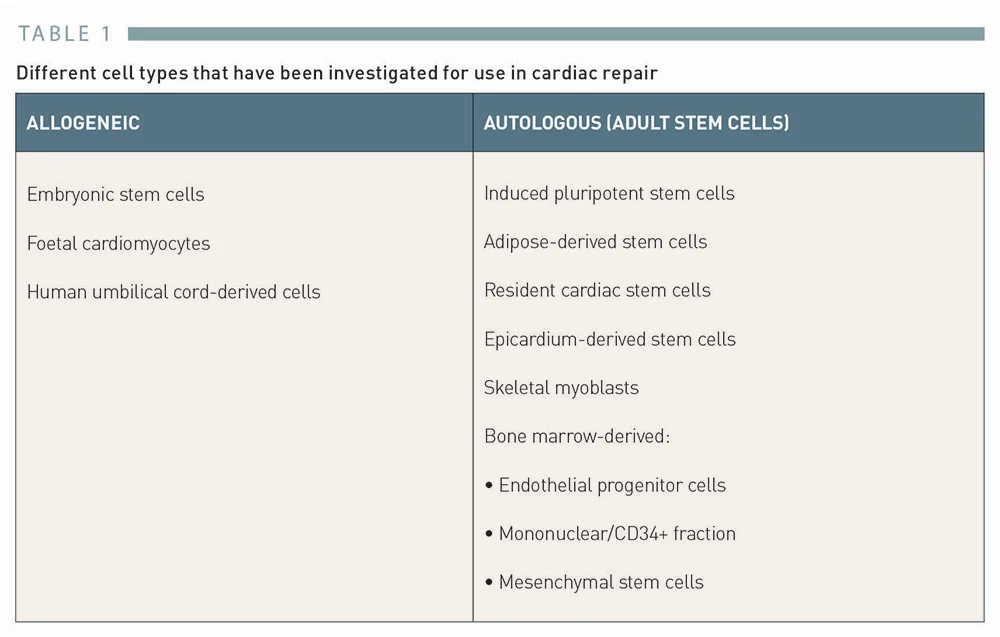

Various cell types have been explored for cardiac repair and are classified as either allogeneic or autologous in origin (Table 1).

已探索了多种细胞类型用于心脏修复,并根据其来源分为同种异体或自体细胞(表 1)。

ALLOGENEIC | AUTOLOGOUS (ADULT STEM CELLS) |

|---|---|

Embryonic stem cells | Induced pluripotent stem cells |

Foetal cardiomyocytes | Adipose-derived stem cells |

Human umbilical cord-derived cells | Resident cardiac stem cells |

Epicardium-derived stem cells | |

Skeletal myoblasts | |

Bone marrow-derived:

|

# Allogeneic cell types 同种异体细胞类型

# Embryonic stem cells ESCs 胚胎干细胞

Given that multiple cell types are generated from a single ESC origin during embryonic development, this cell type’s potential for cardiac repair is self-evident.

鉴于在胚胎发育过程中,多种细胞类型均由单一的 ESC 起源产生,这种细胞类型在心脏修复方面的潜力不言而喻。

ESCs have diverse potential and their differentiation can be controlled to produce specific cell types useful for clinical application.

ESCs 具有多种潜能,其分化可通过控制来产生对临床应用有用的特定细胞类型。

However, their potential is counterbalanced by several significant drawbacks: the collection of cells from embryos raises ethical concerns, implanted cells may require immunosuppression in recipients to prevent rejection and, lastly, their potential for growth and differentiation can also result in tumour formation.

然而,其潜力受到几项重大缺点的制约:从胚胎中收集细胞引发伦理争议,植入的细胞可能需要接受者进行免疫抑制以防止排斥反应,最后,它们在生长和分化方面的潜能也可能导致肿瘤形成。

Recently, the concept of using human-derived ESCs was tested in a small study which engrafted cells onto the heart using a fibrin patch during bypass surgery [1].

近期,一项小型研究检验了利用人源胚胎干细胞的概念,在心脏搭桥手术中通过纤维蛋白贴片将细胞移植到心脏上。

An improvement in cardiac function and symptoms was demonstrated, however larger controlled studies are needed to understand the true benefits of this approach.

这种方法改善了心脏功能和症状,但要了解这种方法的真正益处,还需要进行更大规模的对照研究。

Therefore, although ESCs have significant capacity for cardiac repair, the problems inherent with their use mean that researchers have focussed on ASCs.

因此,尽管胚胎干细胞 ESCs 在心脏修复方面具有显着潜力,但其使用中固有的问题使得研究人员将焦点转向了成体干细胞 ASCs。

# Foetal cardiomyocytes 胎儿心肌细胞

Foetal cardiomyocytes were one of the first cell types to be investigated as a candidate for cardiac repair. Animal studies demonstrated that foetal cardiomyocyte transplantation improved the function of ischaemic and globally failing hearts [11] , [12].

胎儿心肌细胞是最早被研究用于心脏修复的候选细胞类型之一。动物研究表明,胎儿心肌细胞移植可改善缺血性和整体衰竭心脏的功能。

However, the use of foetal cardiomyocytes, like the use of ESCs, raises concerns regarding availability, immunogenicity and ethics.

然而,使用胎儿心肌细胞和使用 ESCs 一样,都会引起对可用性、免疫原性和伦理方面的担忧。

Therefore, other cell types have surpassed these as likely candidates for cardiac repair.

因此,其他类型的细胞已超越这些细胞,成为心脏修复的可能候选细胞。

# Human umbilical cord-derived stem cells hUCSCs 人脐带源干细胞

Umbilical cord blood (blood which remains in the placenta and the attached umbilical cord after childbirth) is a potent source of haematopoietic progenitor cells.

脐带血(分娩后残留在胎盘和脐带中的血液)是造血祖细胞的重要来源。

Human umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells are currently used clinically to repopulate bone marrow in the treatment of bone marrow disorders such as acute leukaemia.

人类脐带血单个核细胞目前临床用于治疗骨髓疾病,如急性白血病,以重建骨髓。

Cord blood also contains a large number of non-haematopoietic progenitor cells which rarely express HLA class II antigens and appear to be immunologically naïve, thus reducing the risk of rejection.

脐带血还包含大量非造血祖细胞,这些细胞很少表达 HLA II 类抗原,并且似乎在免疫学上处于未激活的初始状态,从而降低了排斥反应的风险。

They are an accessible cell type (as they do not need to be harvested from a patient), they can be isolated and expanded in culture and they have a similar therapeutic potential to mesenchymal stem cells (they have been shown to be anti-fibrotic, pro-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory).

它们是一种易于获取的细胞类型(无需从患者身上采集),可在培养中分离和扩增,且具有与间充质干细胞类似的潜在治疗价值(已被证明具有抗纤维化、促血管生成和抗炎作用)。

Human umbilical cord-derived cells, therefore, provide an attractive off-the-shelf option for regenerative therapy [13] , [14].

因此,人类脐带来源的细胞为再生疗法提供了一种诱人的即用型选择。

In animal models of acute myocardial infarction, the injection of human umbilical cord-derived cells has been associated with significant reductions in infarct size, particularly when given by the intramyocardial route [15].

在急性心肌梗塞动物模型中,注射人脐源性细胞可显著缩小梗塞面积,尤其是通过心肌内途径注射时。

Colicchia and colleagues have summarised the preclinical and clinical data for umbilical cord-derived cells in cardiovascular disease [16].

Colicchia 及其同事总结了脐带来源细胞治疗心血管疾病的临床前和临床数据。

A growing number of clinical trials are adopting umbilical cord-derived cells and have shown promising results in cardiac diseases, including acute myocardial infarction [17] , [18] and chronic heart failure [19] , [20] , [21] , [22] , [23] , [24].

越来越多的临床试验采用脐带来源的细胞,在包括急性心肌梗死和慢性心力衰竭在内的多种心脏疾病中,展现了令人鼓舞的效果。

# Autologous cell types 自体细胞类型

Unlike ESCs, autologous adult stem cells are virtually free from the risks of teratoma formation and immune rejection; however, their potential for differentiation is more limited.

与胚胎干细胞 ESCs 不同,自体成体干细胞几乎不存在畸胎瘤形成和免疫排斥的风险;然而,其分化潜能相对有限。

The types of adult cells that have been studied include induced pluripotent stem cells, adipose-derived stem cells, tissue-resident cardiac stem cells, skeletal myoblasts, mesenchymal stem cells, circulating endothelial progenitor cells and, most commonly, bone marrow-derived mononuclear progenitor cells.

已研究的成年细胞类型包括诱导多能干细胞、脂肪源性干细胞、组织驻留心脏干细胞、骨骼肌成肌细胞、间充质干细胞、循环内皮祖细胞,以及最常见的骨髓来源单核祖细胞。

# Induced pluripotent stem cells iPSCs 诱导多能干细胞

An exciting alternative to ESCs is emerging in the form of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).

诱导多能干细胞(iPSCs)作为一种激动人心的替代方案,正逐渐崭露头角,成为胚胎干细胞 ESCs 的有力竞争者。

These are adult stem cells (differentiated somatic cells) that have been successfully reprogrammed back to an undifferentiated pluripotent state through the insertion of regulatory genes (e.g. Oct3/4, Sox2, KL4 and c-Myc) [25] , [26] , [27].

iPSCs 源于成熟的成体干细胞(即已分化的体细胞),通过植入调控基因(如 Oct3/4、Sox2、KL4 和 c-Myc),成功地被重新编程回到未分化的多能状态。

These cells have the same morphological phenotype as ESCs and have been demonstrated in vivo and in vitro to have the same differentiation potential (i.e. the ability to form all three germ cell layers).

这些细胞与 ESCs 具有相同的形态表型,并在体内外实验中证实了它们具有相同的分化潜能(即形成全部三个胚层的细胞层的能力)。

Functioning cardiomyocytes have already been produced from iPSCs, demonstrating their potential for use in cardiovascular regenerative medicine [28].

已成功从 iPSCs 生成功能性心肌细胞,展示了其在心血管再生医学中的应用潜力。

Despite the potential to produce patient-individualised iPSCs, there are problems that need to be solved before they can be used in clinical trials.

尽管具备生成患者个性化 iPSCs 的潜力,但在用于临床试验之前,仍需解决一些问题。

The main concern is tumour genesis as most iPSC lines have been derived by inserting putative oncogenes using integrating retroviruses, e.g. lentiviruses, into the host genome which can cause cancer.

最令人担忧的是肿瘤发生,因为大多数 iPSC 品系都是通过使用整合逆转录病毒(如慢病毒)在宿主基因组中插入可能致癌的基因而获得的。

One mouse study demonstrated that up to 20% of offspring derived using iPSCs developed tumours [29].

一项小鼠研究表明,利用 iPSCs 获得的子代中,最高达 20% 出现了肿瘤。

One further practical barrier to the clinical use of iPSCs is the difficulty in producing enough cells for therapeutic purposes.

临床应用诱导多能干细胞 iPSCs 的另一实际障碍在于,难以产出足够的细胞用于治疗目的。

Experiments to date have shown low conversion rates in the percentage of cells treated compared to those that are successfully induced into an iPSC phenotype - the conversion percentage varies from 0.0006-1% in the literature.

到目前为止的实验表明,在被处理的细胞中,成功转化为诱导多能干细胞 iPSCs 的比例很低,文献中的转化百分比介于 0.0006% 至 1% 之间。

To make matters more difficult, steps taken to combat tumour genesis, e.g. the use of adenoviruses, also significantly impair the conversion rate [30].

更为棘手的是,为防治肿瘤发生而采取的措施,如使用腺病毒,也会大大降低转化率。

Recently, investigators have developed a better understanding of the mechanisms for reprogramming cells and the methods of preventing tumour genesis.

最近,研究人员对细胞重编程的机制和预防肿瘤发生的方法有了更深入的了解。

This has led to the initiation of 4 clinical trials - the results of which are awaited [31].

因此,启动了 4 项临床试验,目前正在等待结果。

Once the aforementioned issues have been resolved, there is a considerable expectation that iPSC production can be scaled up to provide a patient specific source of cardiovascular cells for use in regenerative medicine.

上述问题一旦解决,便有望大幅提升诱导多能干细胞 iPSC 的生产规模,为再生医学提供个性化的心血管细胞来源。

Until these aims are accomplished, the main cell types used will remain adult-derived tissue-specific stem and progenitor cells.

在实现这些目标之前,使用的主要细胞类型仍将是源自成人的组织特异性干细胞和祖细胞。

# Adipose-derived stem cells ADSCs 脂肪源性干细胞

As adipose tissue contains a heterogeneous mixture of endothelial, haematopoietic and mesenchymal progenitor cells which can be harvested easily by liposuction [32], it has been investigated as a source of adult progenitor/stem cells for cardiac repair.

由于脂肪组织含有异质混合的血管内皮、造血及间充质祖细胞,这些细胞可通过吸脂术简易获取,因而被研究作为心脏修复的成年祖细胞 / 干细胞来源。

Preclinical studies have shown that adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) are associated with improved ejection fraction in animal models of myocardial infarction, and neoangiogenesis via paracrine factors has been postulated as a potential mechanism of action [33].

临床前研究表明,在心肌梗死动物模型中,脂肪源性干细胞(ADSCs)与射血分数的改善有关,而通过旁分泌因子的新血管生成被认为是一种潜在的作用机制。

Several clinical trials have explored the safety and feasibility of ADSCs, such as APOLLO [34] and ADVANCE [35] (for acute myocardial infarction), MyStromalCell [36] (for refractory angina) and CSCC_ASC [37] and PRECISE [38] (for chronic ischaemic heart failure).

多项临床试验已探讨了间充质干细胞的安全性与可行性,如 APOLLO 和 ADVANCE(针对急性心肌梗死)、MyStromalCell(针对难治性心绞痛)以及 CSCC_ASC 和 PRECISE (针对慢性缺血性心力衰竭)。

APOLLO demonstrated that liposuction in the acute phase of AMI and the intracoronary infusion of freshly isolated ADSCs is safe and feasible.

APOLLO 证明,在急性心肌梗死急性期进行抽脂并在冠状动脉内输注新鲜分离的 ADSCs 是安全可行的。

At 6 months, cell treatment was associated with a trend towards improved cardiac function, a significant improvement in perfusion defect and a 50% reduction in myocardial scar formation [34].

细胞治疗 6 个月后,心功能有改善趋势,灌注缺损明显改善,心肌瘢痕形成减少 50%。

MyStromalCell evaluated the intramyocardial injection of autologous VEGF-A165 stimulated adipose-derived stromal cells in 60 patients with refractory angina.

MyStromalCell 对 60 名难治性心绞痛患者心肌内注射自体血管内皮生长因子 - A165 刺激的脂肪来源基质细胞进行了评估。

At 6 months, the results demonstrated a within group improvement in exercise time, but this was not significant when compared to placebo [36].

在 6 个月的随访中,结果显示组内患者的运动时间有所改善,但与安慰剂组相比并不显著。

However, at 3 years follow up, the cell-treated patients had improved cardiac symptoms and unchanged exercise capacity, compared to a deterioration in the placebo group [39].

然而,在 3 年的随访中,细胞治疗组患者的心脏症状有所改善,运动能力保持不变,而安慰剂组患者的情况则有所恶化。

PRECISE and CSCC_ASC both demonstrated the safety of ADSCs delivered by the intramyocardial route in ischaemic heart failure, however neither established efficacy.

PRECISE 和 CSCC_ASC 均证明了缺血性心力衰竭患者通过心肌内途径注射 ADSCs 的安全性,但均未确定其疗效。

In PRECISE, the injection of ADSCs in 21 patients did not increase left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) but did stabilise scar size [38].

在 PRECISE 项目中,21 名患者注射 ADSCs 后左心室射血分数(LVEF)没有增加,但瘢痕大小有所稳定。

CSCC_ASC showed a trend towards an improvement in cardiac function at 6-month follow-up: left ventricular end systolic volume decreased whilst LVEF and exercise capacity increased [37].

CSCC_ASC 在 6 个月的随访中显示出心功能改善的趋势:左心室收缩末期容积下降,而 LVEF 和运动能力增加。

SCIENCE, a multicentre Phase II trial, built on these results, randomising 133 patients to an intramyocardial injection of allogeneic CSCC_ASCs or placebo in a 2:1 ratio [40] - the results are still awaited.

SCIENCE 是一项多中心 II 期试验,在这些结果的基础上,对 133 名患者按 2:1 的比例随机进行心肌内注射异体 CSCC_ASCs 或安慰剂,目前仍在等待结果。

# Resident cardiac stem cells 心脏干细胞

The heart was once considered to be a terminally differentiated organ which lacked self-renewal capabilities; however, this dogma has been challenged, particularly with the demonstration of continued cell division within the adult heart following injury such as myocardial infarction [6].

心脏一度被视为终末分化器官,不具备自我更新能力;然而,这一观念已受到挑战,尤其是成年心脏在损伤如心肌梗死后持续细胞分裂的证据出现。

The discovery of myocardial chimeras further increased the suspicion that cardiac stem cells CSCs existed.

心肌嵌合体的发现进一步加深了对心脏干细胞(CSCs)存在的怀疑。

Myocardial chimerism was demonstrated by testing for the presence of the Y chromosome in explanted hearts of male patients who had received female donor hearts.

通过检测接受女性供体心脏的男性患者移植心脏中是否存在 Y 染色体,证实了心肌嵌合现象。

Male derived myocytes and endothelial cells were revealed within the female heart, which was interpreted as representing cardiac repair affected by circulating progenitor cells [41].

在女性心脏中发现了来源于男性的心肌细胞和内皮细胞,这一现象被解读为循环前体细胞影响心脏修复的证据。

A second, similar study, in which the hearts of females who had received male bone marrow were examined for the presence of the Y chromosome, concluded that bone marrow progenitor cells were capable of transit to the heart and its subsequent repair [42].

另一项类似研究中,对接受男性骨髓移植的女性心脏进行 Y 染色体检测,结果显示骨髓前体细胞能够迁移至心脏并参与其修复过程。

The chimera studies suggest that a population of cardiac stem cells recruited from a non-cardiac source such as bone marrow exist.

嵌合体研究提示,源自骨髓等非心脏来源的心脏干细胞群体确实存在。

However, several independent investigators have also presented strong evidence for a resident population of cardiac progenitor cells within the heart.

然而,多位独立研究者亦提供了有力证据,证明心脏内部存在固有的心脏祖细胞群体。

The isolated cardiac stem cells have standard stem cell defining characteristics and can differentiate into multiple cardiac cell lineages such as cardiomyocytes, endothelial and vascular cells [7].

这些分离出的心脏干细胞具备标准干细胞的特征,能够分化成多种心脏细胞系,如心肌细胞、内皮细胞及血管细胞。

These findings have been replicated in animal models and CSCs have been shown to repair and improve cardiac function following myocardial ischaemia [42].

这些发现已在动物模型中得到验证,显示 CSCs 能在心肌缺血后修复并提升心脏功能。

CSCs are therefore an attractive option for clinical trials as they are intrinsically more likely to produce the cells needed to repair the damaged heart.

因此,CSCs 作为临床试验的选择颇具吸引力,因其内在更可能生成修复受损心脏所需的细胞。

However, as they are significantly more difficult to harvest and isolate compared to BMCs, the way ahead may be the activation and stimulation of a patient’s own CSCs rather than a transplantation.

然而,与骨髓细胞(BMCs)相比,CSCs 的采集与分离显着困难,因此未来的研究方向可能是激活和刺激患者自身的心脏干细胞,而不是进行移植。

A harvesting technique has been described that involved obtaining human myocardium from surgical or endomyocardial biopsies which was then partially enzymatically digested and expanded in culture for 14–24 days.

有人描述过一种采集技术,即从外科手术或心内膜活检中获取人体心肌,然后将其部分酶解并在培养基中培养 14-24 天。

Small round cells were seen to bud off from the primary ex-plant and divide in suspension.

可见小圆形细胞从原代移植体上萌出并在悬浮液中分裂。

The isolated cells were then grown in a suspension culture containing a differentiation media which induced the formation of a ball of cells that has been termed a cardiosphere [7].

分离出的细胞随后在含有分化培养基的悬浮培养液中生长,分化培养基诱导细胞球的形成,这种细胞球被称为心球。

When cardiospheres were grown in co-culture with rat neonatal cardiomyocytes, approximately 20% of cardiospheres were seen to contract spontaneously.

当心球与大鼠新生心肌细胞共同培养时,大约 20% 的心球会自发收缩。

Moreover, spontaneous calcium transients were seen in a small percentage of these contracting cells.

此外,在这些收缩的细胞中,有一小部分出现了自发的钙瞬态。

Human cardiosphere-derived cells (CDCs), when injected into the border zone of a mouse model of myocardial infarction, engrafted and migrated into the infarct zone.

将人心球衍生细胞(CDCs)注射到小鼠心肌梗死模型的边缘区后,它们会移植并迁移到梗死区。

After 20 days, the percentage of viable myocardium within the infarct zone was greater in the cell-treated group than in the fibroblast-treated or control group.

20 天后,细胞处理组心肌梗死区内存活心肌的百分比高于成纤维细胞处理组或对照组。

Likewise, echocardiography revealed a higher LVEF in the cardiosphere-treated group (42.8±3.3%) than in the fibroblast-treated (25.0±2.0%, p<0.01) or control group (26.0±1.8%, p<0.01) [43].

同样,超声心动图显示,心球处理组的 LVEF(42.8±3.3%)高于成纤维细胞处理组(25.0±2.0%,p<0.01)或对照组(26.0±1.8%,p<0.01)。

Several clinical trials have demonstrated safety, feasibility and promising efficacy results using cardiac-derived cells.

多项临床试验表明,使用心源性细胞具有安全性、可行性和良好的疗效。

CADUCEUS was the first trial to use an intracoronary infusion of cardiosphere-derived stem cells.

CADUCEUS 是首个使用冠状动脉内输注心源性干细胞的试验。

Autologous CDCs (12.5 to 25 x 106) grown from endomyocardial biopsy specimens were infused via the intracoronary route in 17 patients with left ventricular dysfunction 1.5 to 3 months after myocardial infarction.

心肌梗塞后 1.5 至 3 个月,17 名左心室功能障碍患者通过冠状动脉内途径输注了从心内膜活检标本培育的自体 CDC(12.5 至 25 x 106)。

At 1 year, preliminary indications of bioactivity included decreased scar size, increased viable myocardium and improved regional function of the infarcted myocardium [44].

1 年后,生物活性的初步迹象包括疤痕缩小、存活心肌增加以及梗死心肌的区域功能得到改善。

CAREMI was the first randomised clinical trial to demonstrate the safety of allogeneic cardiac stem cells in the acute phase of STEMI; however, the trial was too small to report on efficacy endpoints [45].

CAREMI 是首个证明异体心脏干细胞在 STEMI 急性期安全性的随机临床试验;但该试验规模太小,无法报告疗效终点。

More recently, ALLSTAR treated 134 patients (in a 2:1 ratio) with LVEF ≤45% and LV scar size ≥15% of LV mass (as assessed by MRI) with either an intracoronary infusion of allogeneic CDCs or placebo 4-12 weeks post-MI.

最近,ALLSTAR 对 134 名 LVEF≤45%、左心室瘢痕大小≥左心室质量 15%(由核磁共振成像评估)的患者(按 2:1 比例)进行了治疗,患者在心肌梗死后 4-12 周可选择冠状动脉内输注异体 CDC 或安慰剂。

The trial was stopped due to the low probability of meeting its primary efficacy endpoint (relative percentage change in infarct size at 12 months post-infusion) after an interim analysis at 6 months.

在 6 个月的中期分析后,由于达到主要疗效终点(输注后 12 个月梗死面积的相对百分比变化)的可能性较低,该试验被终止。

The trial did however meet the primary safety endpoint (with no events at the time of CDC infusion or during the first month, including immunological surveillance) and showed a reduction in LV volumes and NT-proBNP - demonstrating the disease-modifying bioactivity of CDCs [46].

不过,该试验达到了主要安全性终点(输注 CDC 时或第一个月内未发生任何事件,包括免疫监测),并显示左心室容积和 NT-proBNP 减少,这证明 CDC 具有改变疾病的生物活性。

DYNAMIC tested the intracoronary infusion of allogeneic CDCs in 14 patients with dilated cardiomyopathy.

DYNAMIC 对 14 名扩张型心肌病患者进行了异体 CDC 冠状动脉内输注试验。

The study demonstrated an improvement in ejection fraction, left ventricular end-systolic volume, Quality of Life scores and NYHA class at 6 months (the improvements in ejection fraction and Quality of Life scores remained significant at 12 months) [47].

研究显示,6 个月后,射血分数、左室收缩末期容积、生活质量评分和 NYHA 分级均有改善(12 个月后,射血分数和生活质量评分仍有显著改善)。

A combination of mesenchymal and c-kit+ cardiac stem cells was tested in CONCERT-HF - a Phase II trial using a transendocardial injection in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy [48].

在 CONCERT-HF 二期试验中,研究人员测试了间充质细胞与 c-kit + 心脏干细胞的组合,采用经心内膜注射法应用于缺血性心肌病患者。

Although there was some evidence of efficacy, the trial was not definitive in establishing the role of this combination therapy and further exploration of this approach is unlikely [49].

尽管某些证据显示其有效性,但该试验尚不足以明确确立这种联合疗法的作用,且进一步深入探索此方法的前景不明。

In summary, although cardiac-derived cells have considerable theoretical advantages over other cell types, the clinical trials have not reflected this with a strong enough efficacy signal to counterbalance the practical issues.

总之,尽管源自心脏的细胞在理论上相较于其他细胞类型具有显着优势,但临床试验并未充分体现这一优势,以抵消其实际问题。

Furthermore, controversies surrounding work conducted using this cell type have damaged the field and make it difficult to pursue this line of research [50].

此外,围绕使用此类细胞进行的研究工作产生的争议已对该领域造成损害,使得这一研究方向的推进变得困难重重。

# Epicardium-derived progenitor cells EPDCs 心外膜来源的祖细胞

As mentioned previously, the zebrafish can fully regenerate its heart after injuring up to 20% of the ventricle 7. Experimental evidence suggests that this regeneration may occur through the limited dedifferentiation of existing cardiomyocytes followed by proliferation 52, and through the activation and expansion of surrounding epicardial tissue which supports the regenerating myocardium 53. These studies in zebrafish suggest that the epicardium may play an important role not only in adult heart repair, but also during the continuous growth of the adult heart 54. A subset of epicardium-derived progenitor cells (EPDCs), expressing known markers of stem cells (i.e. c-kit and CD34), have been identified in the subepicardial space of foetal and adult human hearts 55. Experimental studies have demonstrated that EPDCs have the potential to differentiate into cardiomyocytes 56, and the intramyocardial injection of human EPDCs in a mouse model of myocardial infarction has been shown to improve cardiac function 57 - supporting the hypothesis that EPDCs may play an important role in cardiac repair. The question arises as to why human EPDCs remain dormant following myocardial injury, and current work is focusing on whether paracrine factors may play a role in activating these cells. A potential stimulus has been identified in the form of thymosin β4 (Tβ4), an actin monomer-binding protein which has been shown to activate EPDCs to a pluripotent state, possibly by an epigenetic effect (a chemical change to DNA which alters gene expression) 58. In a landmark experiment, the pre-treatment of mice with Tβ4 prior to inducing a myocardial infarct led to the activation of EPDCs which underwent cardiomyocyte differentiation, and infarct size and overall ejection fraction were significantly better in the treated mice compared to controls 59. This study provides evidence that the activation and up-regulation of the heart’s own repair mechanism may be possible without the need for additional biological therapy. Despite the initial promising data, a Phase II clinical study (NCT01311518) evaluating the safety and efficacy of injectable Tβ4 in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction was suspended due to issues with GMP compliance in the drug manufacturing process. Unfortunately, despite the initial promise, the use of Tβ4 as a regenerative medical therapy for the treatment of cardiovascular disease is not part of ongoing trials.

# References

Menasché P, Vanneaux V, Hagège A, Bel A, Cholley B, Parouchev A, Cacciapuoti I, Al-Daccak R, Benhamouda N, Blons H, Agbulut O, Tosca L, Trouvin JH, Fabreguettes JR, Bellamy V, Charron D, Tartour E, Tachdjian G, Desnos M, Larghero J. Transplantation of Human Embryonic Stem Cell–Derived Cardiovascular Progenitors for Severe Ischemic Left Ventricular Dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:429-38.Link ↩︎ ↩︎

Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, McMurray JJV, Ponikowski P, Poole-Wilson PA, Strömberg A, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Atar D, Hoes AW, Keren A, Mebazaa A, Nieminen M, Priori SG, Swedberg K, Vahanian A, Camm J, De Caterina R, Dean V, Funck-Brentano C, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Zamorano JL, Auricchio A, Bax J, Böhm M, Corrà U, Della Bella P, Elliott PM, Follath F, Gheorghiade M, Hasin Y, Hernborg A, Jaarsma T, Komajda M, Kornowski R, Piepoli M, Prendergast B, Tavazzi L, Vachiery JL, Verheugt FWA, Zannad F. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2388-42.Link ↩︎

The Heart Failure Policy Network. The handbook of multidisciplinary and integrated heart failure care. London: HFPN. 2018.Link ↩︎

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. xHealth at a glance: Europe 2018. Paris: OECD/EU. 2018.Link ↩︎

Cook C, Cole G, Asaria P, Jabbour R, Francis DP. The annual global economic burden of heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2014;171:368-76.Link ↩︎

Bergmann O, Zdunek S, Felker A, Salehpour M, Alkass K, Bernard S, Sjostrom SL, Szewczykowska M, Jackowska T, Dos Remedios C, Malm T, Andrä M, Jashari R, Nyengaard JR, Possnert G, Jovinge S, Druid H, Frisén J. Dynamics of Cell Generation and Turnover in the Human Heart. Cell. 2015;161:1566–75.Link ↩︎ ↩︎

Messina E, De Angelis L, Frati G, Morrone S, Chimenti S, Fiordaliso F, Salio M, Battaglia M, Latronico MVG, Coletta M, Vivarelli E, Frati L, Cossu G, Giacomello A. Isolation and expansion of adult cardiac stem cells from human and murine heart. Circ Res. 2004;95:911–21.Link ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Poss KD, Wilson LG, Keating MT. Heart regeneration in zebrafish. Science. 2002;298:2188–90.Link ↩︎

Ferrari G, Cusella-De Angelis G, Coletta M, Paolucci E, Stornaiuolo A, Cossu G, Mavilio F. Muscle regeneration by bone marrow-derived myogenic progenitors. Science. 1998;279:1528-30.Link ↩︎

Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, Henegariu O, Hwang S, Gardner R, Neutzel S, Sharkis SJ. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell. 2001;105:369-77.Link ↩︎

Scorsin M, Hagege AA, Marotte F, Mirochnik N, Copin H, Barnoux M, Sabri A, Samuel JL, Rappaport L, Menasché P. Does transplantation of cardiomyocytes improve function of infarcted myocardium. Circulation. 1997;96:188-93.Link ↩︎

Li RK, Jia ZQ, Weisel RD, Mickle DAG, Zhang J, Mohabeer MK, Rao V, Ivanov J. Cardiomyocyte transplantation improves heart function. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;62:654-61.Link ↩︎

Gluckman E. Ten years of cord blood transplantation: From bench to bedside. Br J Haematol. 2009;147:192-9.Link ↩︎

Gluckman E, Ruggeri A, Volt F, Cunha R, Boudjedir K, Rocha V. Milestones in umbilical cord blood transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2011;154:441-7.Link ↩︎

Henning RJ, Burgos JD, Vasko M, Alvarado F, Sanberg CD, Sanberg PR, Morgan MB. Human cord blood cells and myocardial infarction: Effect of dose and route of administration on infarct size. Cell Transplant. 2007;16:907-17.Link ↩︎

Colicchia M, Jones DA, Beirne AM, Hussain M, Weeraman D, Rathod K, Veerapen J, Lowdell M, Mathur A. Umbilical cord–derived mesenchymal stromal cells in cardiovascular disease: review of preclinical and clinical data. Cytotherapy. 2019;21:1007-18.Link ↩︎

Musialek P, Mazurek A, Jarocha D, Tekieli L, Szot W, Kostkiewicz M, Banys RP, Urbanczyk M, Kadzielski A, Trystula M, Kijowski J, Zmudka K, Podolec P, Majka M. Myocardial regeneration strategy using Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cells as an off-the-shelf ‘unlimited’ therapeutic agent: Results from the acute myocardial infarction first-in-man study. Postep w Kardiol Interwencyjnej. 2015;11:100-7.Link ↩︎

Gao LR, Chen Y, Zhang NK, Yang XL, Liu HL, Wang ZG, Yan XY, Wang Y, Zhu ZM, Li TC, Wang LH, Chen HY, Chen YD, Huang CL, Qu P, Yao C, Wang B, Chen GH, Wang ZM, Xu ZY, Bai J, Lu D, Shen YH, Guo F, Liu MY, Yang Y, Ding YC, Yang Y, Tian HT, Ding QA, Li LN, Yang XC, Hu X. Intracoronary infusion of Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells in acute myocardial infarction: Double-blind, randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2015;13:162.Link ↩︎

Fang Z, Yin X, Wang J, Tian N, Ao Q, Gu Y, Liu Y. Functional characterization of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of systolic heart failure. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:3328-32.Link ↩︎

Bartolucci J, Verdugo FJ, González PL, Larrea RE, Abarzua E, Goset C, Rojo P, Palma I, Lamich R, Pedreros PA, Valdivia G, Lopez VM, Nazzal C, Alcayaga-Miranda F, Cuenca J, Brobeck MJ, Patel AN, Figueroa FE, Khoury M. Safety and efficacy of the intravenous infusion of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells in patients with heart failure: A phase 1/2 randomized controlled trial (RIMECARD trial Randomized clinical trial of intravenous infusion umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells on cardiopathy.). Circ Res. 2017;121:1192-204.Link ↩︎

Li X, Hu Y, Guo Y, Chen Y, Guo D, Zhou H, Zhang F, Zhao Q. Safety and Efficacy of Intracoronary Human Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Treatment for Very Old Patients with Coronary Chronic Total Occlusion. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21:1426-32.Link ↩︎

Zhao XF, Xu Y, Zhu ZY, Gao CY, Shi YN. Clinical observation of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell treatment of severe systolic heart failure. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:3010-7.Link ↩︎

He X, Wang Q, Zhao Y, Zhang H, Wang B, Pan J, Li J, Yu H, Wang L, Dai J, Wang D. Effect of Intramyocardial Grafting Collagen Scaffold with Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Patients with Chronic Ischemic Heart Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2016236.Link ↩︎

Ulus AT, Mungan C, Kurtoglu M, Celikkan FT, Akyol M, Sucu M, Toru M, Gul SS, Cinar O, Can A. Intramyocardial Transplantation of Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Chronic Ischemic Cardiomyopathy: A Controlled, Randomized Clinical Trial (HUC-HEART Trial). Int J Stem Cells. 2020;13:364-76.Link ↩︎

Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors. Cell. 2006;126.Link ↩︎

Aasen T, Raya A, Barrero MJ, Garreta E, Consiglio A, Gonzalez F, Vassena R, Bilić J, Pekarik V, Tiscornia G, Edel M, Boué S, Belmonte JCI. Efficient and rapid generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human keratinocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1276-84.Link ↩︎

Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Fibroblasts by Defined Factors. Cell. 2007;131:681-72.Link ↩︎

Zhang J, Wilson GF, Soerens AG, Koonce CH, Yu J, Palecek SP, Thomson JA, Kamp TJ. Functional cardiomyocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Circ Res. 2009;104:30-41.Link ↩︎

Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:313-7.Link ↩︎

Stadtfeld M, Nagaya M, Utikal J, Weir G, Hochedlinger K. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated without viral integration. Science. 2008;322:945-9.Link ↩︎

Menasché P. Cell Therapy With Human ESC-Derived Cardiac Cells: Clinical Perspectives. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:601560.Link ↩︎

Lin K, Matsubara Y, Masuda Y, Togashi K, Ohno T, Tamura T, Toyoshima Y, Sugimachi K, Toyoda M, Marc H, Douglas A. Characterization of adipose tissue-derived cells isolated with the CelutionTM system. Cytotherapy. 2008;10:417-26.Link ↩︎

Valina C, Pinkernell K, Song YH, Bai X, Sadat S, Campeau RJ, Le Jemtel TH, Alt E. Intracoronary administration of autologous adipose tissue-derived stem cells improves left ventricular function, perfusion, and remodelling after acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2667-77.Link ↩︎

Houtgraaf JH, Den Dekker WK, Van Dalen BM, Springeling T, De Jong R, Van Geuns RJ, Geleijnse ML, Fernandez-Aviles F, Zijlsta F, Serruys PW, Duckers HJ. First experience in humans using adipose tissue-derived regenerative cells in the treatment of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:539-40.Link ↩︎ ↩︎

Duckers HJ, Musialiek P, Dudek D, Kochman J, Kesten S, Pompilio G. Abstract 16129: Feasibility and Safety of Treatment With an Intracoronary Infusion of Adipose Derived Regenerative Cells (ADRC) in Patients With an Acute ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (ADVANCE study). Circulation. 2014;130:A16129.Link ↩︎

Qayyum AA, Mathiasen AB, Mygind ND, Kühl JT, Jørgensen E, Helqvist S, Elberg JJ, Kofoed KF, Vejlstrup NG, Fischer-Nielsen A, Haack-Sørensen M, Ekblond A, Kastrup J. Adipose-Derived Stromal Cells for Treatment of Patients with Chronic Ischemic Heart Disease (MyStromalCell Trial): A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Study. Stem Cells Int. 2017;2017:5237063.Link ↩︎ ↩︎

Kastrup J, Haack-Sørensen M, Juhl M, Harary Søndergaard R, Follin B, Drozd Lund L, Mønsted Johansen E, Ali Qayyum A, Bruun Mathiasen A, Jørgensen E, Helqvist S, Jørgen Elberg J, Bruunsgaard H, Ekblond A. Cryopreserved Off-the-Shelf Allogeneic Adipose-Derived Stromal Cells for Therapy in Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease and Heart Failure—A Safety Study. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6:1963-71.Link ↩︎ ↩︎

Perin EC, Sanz-Ruiz R, Sánchez PL, Lasso J, Pérez-Cano R, Alonso-Farto JC, Pérez-David E, Fernández-Santos ME, Serruys PW, Duckers HJ, Kastrup J, Chamuleau S, Zheng Y, Silva G V., Willerson JT, Fernández-Avilés F. Adipose-derived regenerative cells in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy: The PRECISE Trial. Am Heart J. 2014;168:88-95.Link ↩︎ ↩︎

Qayyum AA, Mathiasen AB, Helqvist S, Jørgensen E, Haack-Sørensen M, Ekblond A, Kastrup J. Autologous adipose-derived stromal cell treatment for patients with refractory angina (MyStromalCell Trial): 3-years follow-up results. J Transl Med. 2019;17:360.Link ↩︎

Paitazoglou C, Bergmann MW, Vrtovec B, Chamuleau SAJ, van Klarenbosch B, Wojakowski W, Michalewska-Włudarczyk A, Gyöngyösi M, Ekblond A, Haack-Sørensen M, Jaquet K, Vrangbæk K, Kastrup J, Ciosek J, Dworowy S, Jadczyk T, Kozłowski M, Nadrowski P, Sagalski R, Schlegel E, Schmidt A, Sikora A, Skiba D, Traxler D, Qayyum AA, Mathiasen AB. Rationale and design of the European multicentre study on Stem Cell therapy in IschEmic Non-treatable Cardiac diseasE (SCIENCE). Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:1032-41.Link ↩︎

Höcht-Zeisberg E, Kahnert H, Guan K, Wulf G, Hemmerlein B, Schlott T, Tenderich G, Körfer R, Raute-Kreinsen U, Hasenfuss G. Cellular repopulation of myocardial infarction in patients with sex-mismatched heart transplantation. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:749-58.Link ↩︎

Oh H, Bradfute SB, Gallardo TD, Nakamura T, Gaussin V, Mishina Y, Pocius J, Michael LH, Behringer RR, Garry DJ, Entman ML, Schneider MD. Cardiac progenitor cells from adult myocardium: Homing, differentiation, and fusion after infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12313-8.Link ↩︎

Smith RR, Barile L, Cho HC, Leppo MK, Hare JM, Messina E, Giacomello A, Abraham MR, Marbán E. Regenerative potential of cardiosphere-derived cells expanded from percutaneous endomyocardial biopsy specimens. Circulation. 2007;115:896-908.Link ↩︎

Malliaras K, Makkar RR, Smith RR, Cheng K, Wu E, Bonow RO, Marbán L, Mendizabal A, Cingolani E, Johnston P V., Gerstenblith G, Schuleri KH, Lardo AC, Marbán E. Intracoronary cardiosphere-derived cells after myocardial infarction: Evidence of therapeutic regeneration in the final 1-year results of the CADUCEUS trial (CArdiosphere-derived aUtologous stem CElls to reverse ventricular dysfunction). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:110-22.Link ↩︎

Fernández-Avilés F, Sanz-Ruiz R, Bogaert J, Casado Plasencia A, Gilaberte I, Belmans A, Fernández-Santos ME, Charron D, Mulet M, Yotti R, Palacios I, Luque M, Sádaba R, San Román JA, Larman M, Sánchez PL, Sanchís J, Jiménez MF, Claus P, Al-Daccak R, Lombardo E, Abad JL, DelaRosa O, Corcóstegui L, Bermejo J, Janssens S. Safety and Efficacy of Intracoronary Infusion of Allogeneic Human Cardiac Stem Cells in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Left Ventricular Dysfunction. Circ Res. 2018;123:579-89.Link ↩︎

Makkar RR, Kereiakes DJ, Aguirre F, Kowalchuk G, Chakravarty T, Malliaras K, Francis GS, Povsic TJ, Schatz R, Traverse JH, Pogoda JM, Smith RR, Marbán L, Ascheim DD, Ostovaneh MR, Lima JAC, DeMaria A, Marbán E, Henry TD. Intracoronary ALLogeneic heart STem cells to Achieve myocardial Regeneration (ALLSTAR): A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded trial. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3451-8.Link ↩︎

Chakravarty T, Henry TD, Kittleson M, Lima J, Siegel RJ, Slipczuk L, Pogoda JM, Smith RR, Malliaras K, Marbán L, Ascheim DD, Marbán E, Makkar RR. Allogeneic cardiosphere-derived cells for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: The Dilated cardiomYopathy iNtervention with Allogeneic MyocardIally-regenerative Cells (DYNAMIC) trial. EuroIntervention. 2021;16:E293-300.Link ↩︎

Bolli R, Mitrani RD, Hare JM, Pepine CJ, Perin EC, Willerson JT, Traverse JH, Henry TD, Yang PC, Murphy MP, March KL, Schulman IH, Ikram S, Lee DP, O’Brien C, Lima JA, Ostovaneh MR, Ambale-Venkatesh B, Lewis G, Khan A, Bacallao K, Valasaki K, Longsomboon B, Gee AP, Richman S, Taylor DA, Lai D, Sayre SL, Bettencourt J, Vojvodic RW, Cohen ML, Simpson L, Aguilar D, Loghin C, Moyé L, Ebert RF, Davis BR, Simari RD. A Phase II study of autologous mesenchymal stromal cells and c-kit positive cardiac cells, alone or in combination, in patients with ischaemic heart failure: the CCTRN CONCERT-HF trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:661-74.Link ↩︎

Bayes-Genis A. The CONCERT-HF trial: a sweet and sour symphony. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:675-6.Link ↩︎

Davis DR. Cardiac stem cells in the post-Anversa era. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:1039-41.Link ↩︎